LOADING TEA-JUNKS AT TSEEN-TANG

(*Vide Vol. I. p. 26. Vol. II. p. 45)

Cover Image: Loading Tea-junks, at Tseen-tang / SuZhou JiangSu China / Drawn by T. Allom Engraved by J.Tingle – ALAMY Image ID:2X55NCM

*Suzhou’s Tseen-tang(Cengtang), located in the Taihu Lake basin, has been an important hub for waterway transportation since ancient times. Throughout history, Cengtang was a bustling commercial port that attracted numerous merchants and traders. The area is also home to many ancient dwellings, temples, and bridges, showcasing the charm of ancient Chinese water-town culture.

The sweat of industry would dry and die,

But for the end it works to.CYMBELINE

ON a tributary to the river of “the Nine Bends,” and in the province of Fokien, is a romantic, rich, and remarkable spot, the resort of tea-factors, and the principal loading-place, in the district, for tea destined for the Canton and other markets. The hills and the valleys here are equally favourable to the production of this staple of China, and the tea-tree itself has been carefully examined, and its peculiarities ascertained by Europeans in this locality, with more minuteness and scrupulosity than elsewhere.

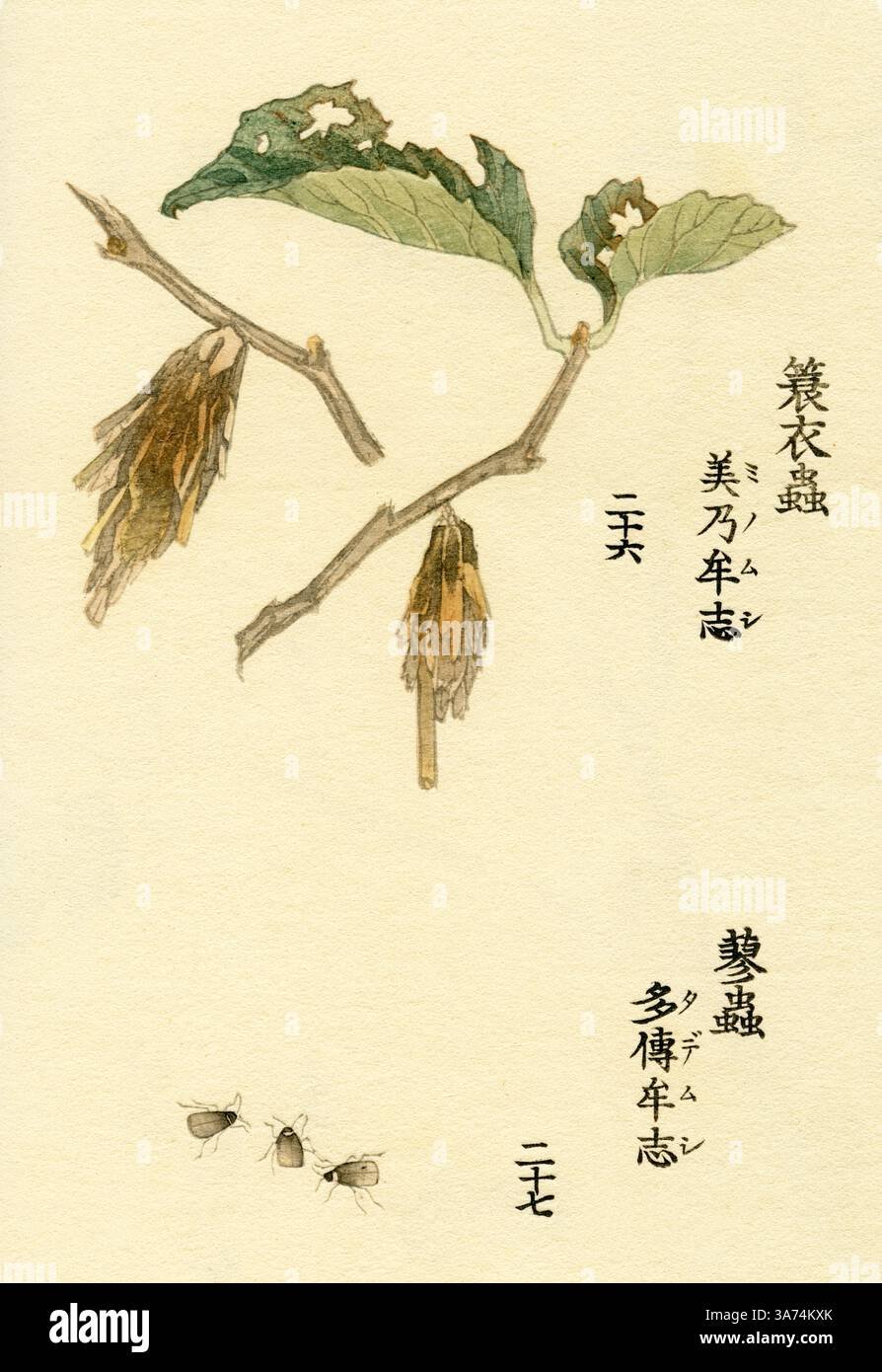

In the process of sowing, several seeds are dropped into a hole made for their reception, the cultivator having learned from experience, the risk of trusting to a single grain. When the plant appears above the surface, it is tended with the utmost care; attacks of insects are jealously provided against, rude visitations of wind cautiously prevented, and, should the tea-farm be distant from the natural stream, skilful irrigation conducts an artificial rivulet through every part of it. The leaf being the product required, every artifice is employed to enable it to attain maturity. For three years, or until the plant has risen to the height of four feet, no crop is gathered; the little tree being permitted to retain all its innate power of self-sustenance; but, having attained this age, gathering is then commenced, and conducted upon the most methodical principles. As the youngest leaves afford the most grateful infusion, it is desirable to gather early, but this must not be done with a precipitation likely to endanger the future vigour of the tree; and hence no leaves are pulled until age has established hardihood. The first shoots, or the appearance of the bud, are covered with hair, and afford the fine flowery Pekoe; should they be permitted to have a few days’ more growth, the hair begins to fall off, the leaf expands, and becomes black-leaf Pekoe. On the same tree, of course, some young shoots occur that present more fleshy and finer leaves, these afford the Souchong; the next in quality will make Campoy; a shade lower, Congou; and the refuse, Fokien Bohea.

Tea-plants are grown in rows about five feet asunder, the intermediate furrows being kept free from weeds, the asylum of insects; and the trees are not allowed to attain a height inconvenient for pickers. Indeed, when the tea-tree reaches its eighth year, it is removed, to make way for a more youthful successor, the produce of old trees being unfit for use. The flowers of the tree, which are white, and resemble the common monthly-rose in form, are succeeded by soft green berries or pods, each enclosing from one to three white seeds. March is the first month in the year for picking, both as to time and quality, and great precautions are observed in this ceremony. The pickers are required to prepare themselves for their task by a specific process. For several weeks previous to the harvest, they take such diet only as may communicate agreeable odours to the skin and breath, and, while gathering, they wear gloves of perfumed leather. Every leaf is plucked separately, but, as practice confers perfection, an expert performer will gather twelve pounds in the course of a day. April is the second season;—leaves gathered in this month afford a coarser and inferior description of tea; they are plucked with fewer ceremonies than those of the preceding crop, but, should a large proportion of small and delicate leaves appear, these are selected, and sold as the produce of the first picking. In May and June inferior kinds are gathered, and even sometimes later. Leaves of the earliest crop are of small size, delicate colour and aromatic flavour, with little fibre and more bitterness; those of the second picking are of a dull green; and the last gatherings are characterized by a still darker shade of the same colour, and a much coarser grain. Quality is influenced by the age of the plantation, by the degree of exposure to which the tree has been accustomed, by the nature of the soil, and the skill of the cultivator.

The leaves when gathered are placed in wide shallow baskets, and during several hours exposed to the wind and the sunshine; they are next removed into deeper baskets, and taken to the curing house, a species of public establishment found in all tea-districts, where the drying process is superintended, either by the owners, or by the servants of the drying-house. A number of stoves generally ranged in a continuous right line, support a series of thin iron plates, or hot hearths. When heated so high that a leaf thrown upon it returns a loud crackling noise, the hearth is prepared for the process. A quantity of leaves is now laid upon the plate, and turned over by means of a brush, with a rapidity sufficient to prevent their being scorched, while they are enduring a considerable degree of heat. When they begin to curl, they are swept off the hearth, and spread out upon a table covered with paper, or some other smooth and fine-textured hands. While another, with large fans, are employed in reducing the temperature suddenly, and thereby accelerating the requisite curling of the tea. The heaps are submitted a second, and even a third time, to the same process, until the manufacturers consider that they are perfectly cooled and properly cured. Coarse kinds, that is, refuse from the two last gatherings, being filled with stronger fibres, and possessing a bitter flavour, are exposed to the steam of hot water, previously to being thrown upon the heated hearth; and if the artist be skilful, their appearance and quality may both be materially improved. For some months, the dried tea remains in baskets in the storehouse of the grower; after which it is once more exposed to a gentle heat, before being carried to market.

An obvious distinction exists between the farmer, or grower, and the manufacturer: the former separates the respective qualities with the utmost care, and disposes of them, in that selected manner, to the manufacturer, either at his own house, or in the most convenient market; the latter removes his purchases to his private factory, and there, taking certain measures from each heap, mixes them together, in proportions producing the exact quality he wishes to give each particular class, or number of chests; the farmer therefore is a separator—the manufacturer, a concentrator. And now the process of planting, rearing, gathering, drying, separating, and mixing being completed, it only remains to pack the preparation into chests, and tread it down sufficiently; in this convenient form it is put on board the junks at Tseen-tang, and other loading-places in the tea-growing countries, and carried to the stores at Canton or Macao.

![[VOL IV] THE VALLEY OF CHUSAN](https://i0.wp.com/arclumiva.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/valley-of-ting-hai-chusan-dinghai-zhoushan-zhejiang-china-drawn-by-t-allom-engraved-by-s-bradshaw-2X55NJ3.jpg?resize=870%2C570&ssl=1)

![[VOL IV] ANCIENT BRIDGE, CHAPOO](https://i0.wp.com/arclumiva.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/ancient-bridge-chapoo-haiyan-jiaxing-zhejiang-china-drawn-by-t-allom-engraved-by-rsands-2X55NHK.jpg?resize=600%2C600&ssl=1)

![[VOL IV] HONG-KONG, FROM KOW-LOON](https://i0.wp.com/arclumiva.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/hong-kong-from-kow-loon-kowloon-hong-kong-china-drawn-by-t-allom-engraved-by-sfisher-2X55NGM.jpg?resize=600%2C600&ssl=1)

![[VOL IV] CHINESE BOATMAN ECONOMIZING TIME AND LABOUR, POO-KEOU](https://i0.wp.com/arclumiva.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/chinese-boatman-economizing-time-labour-poo-kow-nanjing-jiangsu-china-drawn-by-t-allom-engraved-by-awillmore-2X55NGD.jpg?resize=600%2C600&ssl=1)