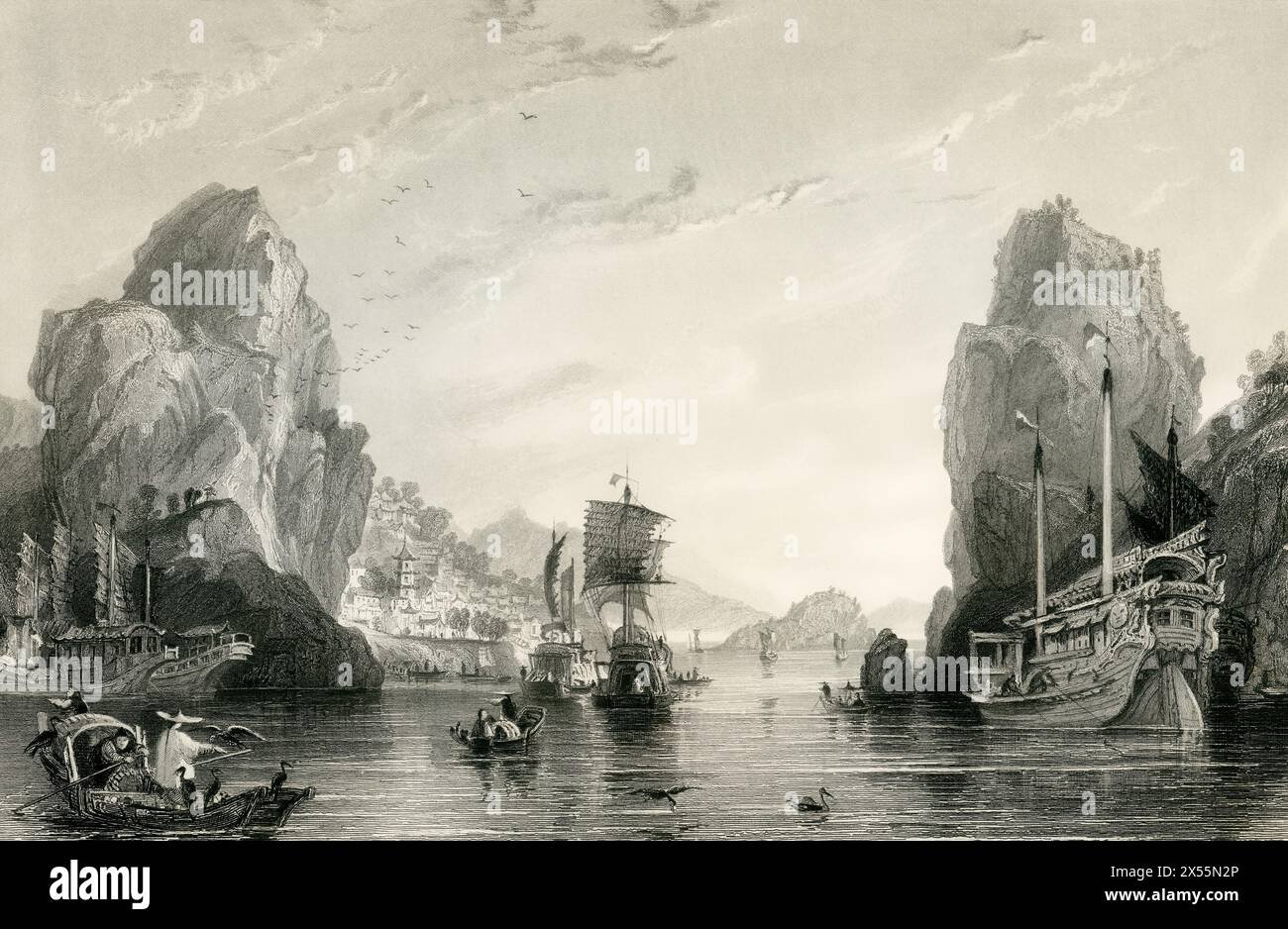

THE SHIHI-MUN, OR ROCK GATES, PROVINCE OF KIANG-NAN

Cover Image: The Shih-mun, or Rock Gates ( Province of Kiang-nan ) / Shimen HuangShan Anhui China / Drawn by T. Allom Engraved by Le Petit – ALAMY Image ID:2X55N2P

*Shih-mun(Shimen) is located in the present-day Heping County(Huang Shan)in Anhui.

For ever glideth on that lovely river:

Laden with early wreaths the creepers twine,

While like the arrows from a royal quiver,

Golden the glaring sunbeams o’er them shine.”L. E. L.

IT is remarkable that people in a primitive state (and notwithstanding their superiority in handicraft, the Chinese do not rise much higher in the scale of nations) possess the truest and most admirable ideas of the picturesque. Presumption seems to be the characteristic of modern taste; agreeable and comfortable associations, of that which prevailed in the olden time. Our abbeys and convents are placed beside the running stream, or on the banks of a navigable river, sheltered from the rude blasts of winter by surrounding forests or impending hills. In all ancient countries, and where the highest degrees of civilization are unknown, domestic architecture is not only suited to the natural features of the landscape, but embosomed recesses, deep and densely-wooded dingle, valleys fertile and well watered, the romantic banks of some rapid but available river, a spot where business and beauty are combined, was uniformly selected as the abode, either of the individual or the community. This grateful and fascinating taste has withered into contempt before the growth of civilization, whose great glory is to level mountains, drain lakes, reclaim the barren wastes, and triumph over nature by erecting on those very sites which she had made the most repulsive, the very noblest works of art.

An instinctive love of the picturesque, a prerogative of the mountaineer in all parts of the world, is peculiarly the Chinaman’s inheritance; and, in the province of Kiang-nan, enriched and adorned by a majestic river, they have indulged their taste for landscape scenery in a manner and degree calculated to raise our estimation of their intellectual qualities. For some miles above and below the Shih-Mun, the river is enclosed between banks abrupt, rocky, but interspersed with patches and plateaus of productive land. The country behind is of a totally contrary character; there a wide-spread morass exists, difficult of drainage from the rocky ridges that form the river’s bed, through which a passage for the surplus waters of the fens can scarce be found. Abandoning this moor to the wild tenants of the earth and skies, the population have flocked to the water’s edge, and possessed themselves of the projecting ledges at the mountain’s foot, the retiring bays at their sheltered base, or the vicinity of some dark pool, whose scaly treasures repay the fisherman for his constant toil. As the junks descend the river the velocity of the current increases, until its maximum is attained between the herculean pillars of the Rock-gates. There the navigation requires much caution, and often the most vigilant, confounded by the suddenness with which the two high pinnacles seem to close over him, and embrace the azure vault of heaven, mistake their distance, and are carried against the rocks. In the surrounding district, limestone prevails very generally, but along the river’s side it appears to recline on a species of breccia: it would not be untrue to characterize the stone in the immediate vicinity of the Shih-Mun as marble, although the natives do not place any value on it for decorative purposes, neither do they burn it into lime.

On either side, and just below the rude rocky pillars that contract the passage, small coves, of great depth and perfect shelter, afford safe anchorage for merchant-vessels; and there the trading junk is generally seen moored to the natural quay, the steadfast cliff; the contracted channel giving a violent and powerful efficacy to the volume of waters, which have consequently worked an immense depth here for their transit. In this deep basin, multitudes of fish collect, and render their capture, by trained fishing-birds, an achievement both easy and profitable. The privilege of fishing between the Rock-gates is rented at a very high price from the local government. These lofty peaks, that pierce the clouds, derive the epithet “Shih-Mun” from the termination of a magnificent scene, so inclined to the direct view of the Rock-gates as to be incapable of introduction in the illustration. Its beauties, its solemnities, its horrors, have been described in bold and highly coloured language by native poets and tourists; nor has national prejudice, in this instance, outstepped the limits of veracity. Entering a deep, dark, close ravine, the opposite sides of which attain at least a thousand feet in height, with an intervening space of comparative insignificance, the traveller proceeds along his gloomy way, unable to distinguish, save by the occasional sparkling and foaming of the torrent that tumbles and roars in the abyss below him. Having reached the length of a li, or more, he enters “the valley of mist,” where he becomes enveloped in a thick vapour, filling the entire gulf which the torrent has hollowed out from the mountain’s bosom by the labour of four thousand years; and, if he not deterred by the humidity of the strange atmosphere, but perseveres to the end, in a winding way he will behold the origin of the dewy drapery that hangs over and around him—a splendid cataract, some hundred feet in height, falling over the very edge of the cliff; the spot he stands on, and the circular hollow all around him, being dimly lighted by the rays that pierce through the green waters, at the spot where they turn over the ledge of the summit. With this beautiful hue of green, the poetical historians of the wonders of the Shih-Mun are familiarly acquainted. They boast of having witnessed its lustre in the valley of mist, and compare its verdure to the Lan, the plant from which the rich colour employed in dyeing is extracted. They speak of the blue mountains, the green cataract, and the hillock of Heen-Yüen, an ancient king of Kiang-Nan, and they celebrate the amusements and exploits of his rural life. But his majesty must have been formed of unearthly mould, or else “the greatest amongst mountain streams” had not descended so far into the bowels of the earth, nor yet filled “the ravine of the black stork,” with mists impenetrable and for many miles, in the age when that old Lear of Chinese history is said to have held his court only four li from the Shih-Mun.

![[VOL IV] THE VALLEY OF CHUSAN](https://i0.wp.com/arclumiva.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/valley-of-ting-hai-chusan-dinghai-zhoushan-zhejiang-china-drawn-by-t-allom-engraved-by-s-bradshaw-2X55NJ3.jpg?resize=870%2C570&ssl=1)

![[VOL IV] ANCIENT BRIDGE, CHAPOO](https://i0.wp.com/arclumiva.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/ancient-bridge-chapoo-haiyan-jiaxing-zhejiang-china-drawn-by-t-allom-engraved-by-rsands-2X55NHK.jpg?resize=600%2C600&ssl=1)

![[VOL IV] HONG-KONG, FROM KOW-LOON](https://i0.wp.com/arclumiva.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/hong-kong-from-kow-loon-kowloon-hong-kong-china-drawn-by-t-allom-engraved-by-sfisher-2X55NGM.jpg?resize=600%2C600&ssl=1)

![[VOL IV] CHINESE BOATMAN ECONOMIZING TIME AND LABOUR, POO-KEOU](https://i0.wp.com/arclumiva.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/chinese-boatman-economizing-time-labour-poo-kow-nanjing-jiangsu-china-drawn-by-t-allom-engraved-by-awillmore-2X55NGD.jpg?resize=600%2C600&ssl=1)